Introduction:

For centuries, philosophers have grappled with questions about the nature of knowledge. What is knowledge, and how do we acquire it? These fundamental questions have driven the study of epistemology, a branch of philosophy exploring human knowledge's nature and limits. The origins of epistemology can be traced back to ancient Greek philosophy, where philosophers such as Plato and Aristotle sought to understand the nature of knowledge and its relationship to truth. Pursuing knowledge has been a fundamental concern of human beings throughout history. In this article, we will explore some of the critical theories of knowledge, including rationalism, empiricism, and pragmatism. We will also consider the relationship between Belief and knowledge and the role that evidence and justification play in acquiring knowledge. By the end of this article, readers will have a deeper understanding of the rich history and ongoing discussions in the field of epistemology and the complexities of knowledge acquisition.

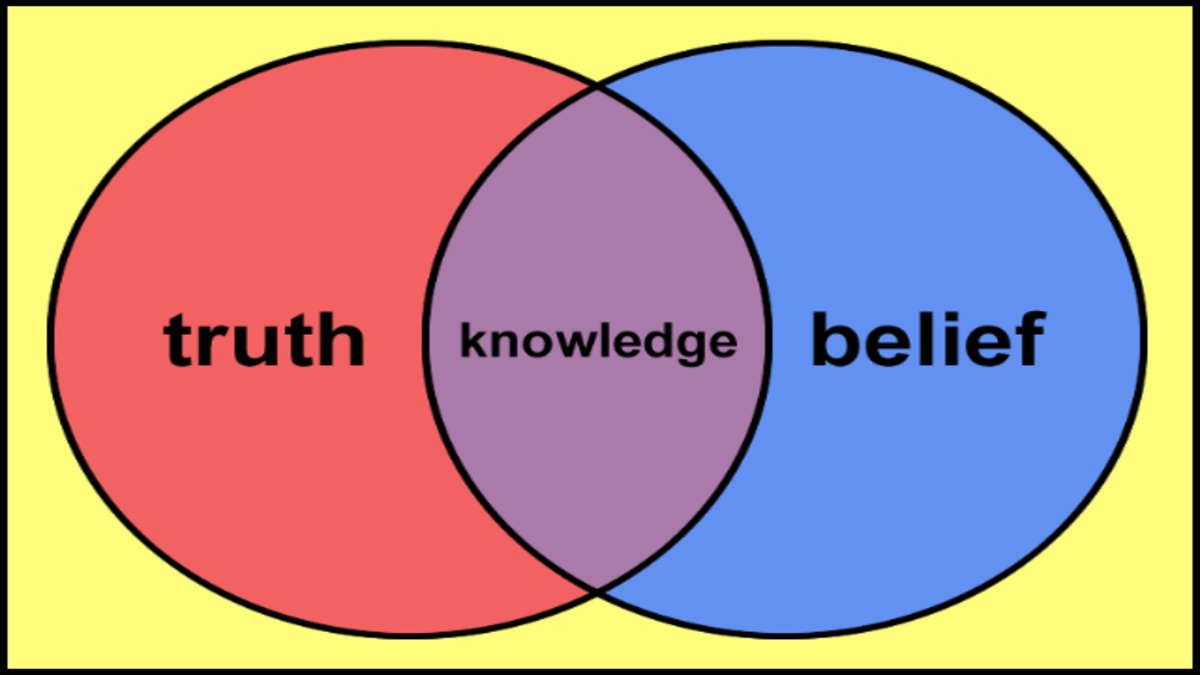

Knowledge, Belief, and Justification are all essential concepts in philosophy that help us understand how we acquire knowledge about the world and evaluate the truth or reliability of our beliefs.

Belief is a mental attitude or state of mind in which a person accepts something as true or accurate—beliefs based on evidence, intuition, authority, or other factors. For example, one might believe vaccinations are safe and effective based on the advice of medical professionals and scientific studies. Biases or cognitive errors can also influence beliefs, so critically evaluating the reasons and evidence for our beliefs is essential.

Justification refers to the reasons or evidence that support a belief. Good reasons or evidence must support a belief to be considered justified. For example, suppose one believes that smoking causes lung cancer. In that case, the person's justification for this Belief might include epidemiological studies that have found a strong correlation between smoking and lung cancer and the scientific mechanisms by which smoking can damage the lungs and lead to cancer. The level of justification required for a belief to be considered knowledge can vary depending on the context and the standards of evidence in a particular field.

In epistemology, knowledge is generally defined as justified true Belief. This statement means that something counts as knowledge if it is accurate and the person holding the Belief has good reasons or evidence to believe it. The concept of knowledge is crucial because it allows us to distinguish between true beliefs based on good reasons or evidence and beliefs based on luck, chance, or other unreliable factors.

Knowledge acquisition is a multifaceted process that relies on various methods and sources. Some of these include:

Sense perception: We acquire knowledge through our senses, such as seeing, hearing, touching, tasting, and smelling. We can observe and experiment with the world to learn about its properties and behavior.

Reasoning: We draw conclusions based on logical or evidential connections between ideas or observations. We can use deductive reasoning, moving from general principles to specific conclusions, or inductive reasoning, from specific observations to general principles.

Testimony: We can gain knowledge from others by listening to their testimony or expertise. For example, we can learn about history from books or lectures or about scientific discoveries from experts in the field.

Intuition: Sometimes, we acquire knowledge through intuition or instinct without necessarily being able to provide reasons or evidence to support our beliefs.

Our acquisition of knowledge is not without limits. In order to avoid unwarranted assumptions and false conclusions, it is crucial to acknowledge these limitations.

Some of the critical limits of our knowledge include the following:

Epistemic skepticism: Some philosophers argue that we cannot have certainty about anything and that there are limits to what we can know. For example, we may not be able to know whether or not we are living in a computer simulation or whether there is an objective reality beyond our senses.

Scientific uncertainty: Scientific knowledge is always provisional and subject to change. We may not be able to know with certainty the causes of complex phenomena like climate change or the ultimate nature of the universe.

Cognitive biases: Our beliefs and knowledge can be influenced by cognitive biases, such as confirmation or availability, leading us to draw incorrect conclusions or maintain false beliefs.

Moral limits: There may be limits to our ability to know certain moral truths, such as the right course of action in complex ethical dilemmas.

Linguistic limits: Our language limits our ability to communicate our knowledge. Some concepts may be difficult to express in words or subject to multiple interpretations.

Historical limits: Our knowledge is also limited by our access to historical records and artifacts. Some events may have been lost to history or may be subject to different interpretations or biases.

Cultural limits: Our cultural context also shapes our knowledge, which can influence what we consider important or relevant knowledge. Some cultures may value different knowledge or ways of knowing than others.

These limits of knowledge demonstrate that there are always gaps and uncertainties in what we know about the world. However, by being aware of these limits and striving to overcome them through critical thinking and rigorous inquiry, we can continue to expand our understanding of the world and improve our ability to make informed decisions.

The interplay between Belief and knowledge illuminates the gaps in our understanding and sheds light on how we acquire knowledge. Let us delve into the intricacies of this relationship.

Not all beliefs we hold can be considered knowledge; some beliefs may be justified but not rise to the level of knowledge. Additionally, conceiving a scenario where we could know something without believing it is not easy. Belief is an essential component of knowledge. In order to know something, we must first believe it to be true. However, not all beliefs that we hold can be considered knowledge. What qualifies as knowledge, a belief must meet specific criteria, such as being justified and true. We might justify our beliefs through reasoning, sensory experience, or testimony from others. However, not all justifications are created equal. Some justifications may be more robust, depending on the context and evidence available.

True Belief is only sometimes sufficient for knowledge. For example, imagine a person correctly guessing the outcome of a coin flip. The person believes that the coin will land on heads, and it does. While the person's Belief is true, it was not justified by any evidence or reasoning, so it cannot be considered knowledge. Beliefs that are justified but not knowledge are sometimes called "Gettier cases," after the philosopher Edmund Gettier famously argued that knowledge is more than just justified true Belief.

For example, imagine that the person sees a clock that reads 3:00 and believes it is 3:00. Unbeknownst to the individual, the clock stopped working at noon, but by coincidence, it happens to be correct when the person looks at it. The individual's Belief is justified (you saw the clock read 3:00), and it is true (the clock did read 3:00), but it is not knowledge since your justification was based on faulty evidence.

Can we know something without believing it?

It is not easy to conceive a scenario where we could know something without believing it. Since Belief is an essential component of knowledge, knowledge requires it. However, there may be cases where we hold beliefs without realizing it, or our beliefs are implicit rather than explicit. Additionally, we may hold beliefs that we are unaware of but somehow influence our actions or decisions.

The role of evidence and justification in acquiring knowledge is crucial. We need good reasons or evidence to justify our beliefs to claim that we know. Beliefs can be justified or unjustified, and knowledge requires justification. The quality and quantity of evidence required to justify a belief can vary depending on the claim's context and nature. Some beliefs may require very little evidence to be justified, while others may require a great deal. The standard for what constitutes sufficient evidence to justify a belief can also change as new evidence becomes available or our understanding of the world evolves. Generally, the more evidence we have to support a belief, the more justified it is. However, it is essential to note that evidence alone does not necessarily lead to knowledge. We also need to ensure that the evidence is reliable and that our methods of acquiring and evaluating evidence are sound. For example, if someone believes that a diet can cure cancer, they may cite anecdotal evidence from people who claim to have been cured. However, more than this kind of evidence is needed to justify the Belief because it is unreliable or scientifically validated.

In contrast, if a large body of scientific research shows that a particular treatment is effective for cancer, that would constitute more reliable and robust evidence to justify the Belief. One of the key features of knowledge is that it is based on evidence and justification. However, this does not necessarily mean our beliefs are always certain or immutable. It is often the case that new evidence or information can challenge our beliefs and lead us to revise them.

For example, people used to believe that the Earth was flat, but with the accumulation of scientific evidence over time, we now know that the Earth is an oblate spheroid. Similarly, our understanding of the nature of light has evolved based on new evidence and experimental findings. This notion suggests that our beliefs are always subject to revision based on new evidence. However, this does not mean we can never be sure about anything. We can sometimes be confident that our beliefs are valid based on the available evidence. For example, we can be highly confident that water freezes at 0 degrees Celsius at sea level based on the extensive experimental evidence that supports this claim.

Similarly, we can be highly confident that smoking causes lung cancer based on the large body of epidemiological and experimental evidence that supports this claim. The degree of certainty we can have about our beliefs depends on the amount and quality of evidence that supports them. If a large amount of high-quality evidence supports a belief, we can be more confident that it is true. However, we should always be open to revising our beliefs if new evidence or information challenges them. This act is what makes knowledge a dynamic and constantly evolving process.

In conclusion, we have explored the fundamental concept of epistemology: the study of knowledge and Belief. We have seen how this field examines the nature of knowledge, its sources, and the conditions necessary for justified Belief. By understanding epistemology, we gain a deeper appreciation of the processes involved in acquiring knowledge and the challenges and limitations inherent in our cognitive abilities.

Moving forward, we will delve deeper into the various theories of epistemology, including their criticisms, objections, and arguments. By doing so, we will gain a better understanding of the complexities of this field and the diverse perspectives that exist within it. Ultimately, this exploration will enable us to approach the study of knowledge and Belief with a more nuanced and critical perspective.